Let's Get Psychophysical - Newsletter #3

Winged Feet and Winged Words

Hello, it’s Kevin. Welcome to Let’s Get Psychophysical.

Every Sunday, I send you 5 things to promote wholeness, integration and “waking up” - rather than fragmentation, dis-integration and falling asleep.

Let me know what you think-feel-do.

Book:

How We Think (1910) by John Dewey

I am reading this because John Dewey was a private pupil of F. Matthias Alexander’s from 1917 onwards. His philosophy of American Pragmatism was influenced by the practical technique he learned from Alexander. He also wrote the prefaces for three of his four books.

Dewey’s book is extremely clear and helpful on the close relation between thinking and action… but is also quite dry and boringly written. So I will discuss a quote that jumped out at me:

“The exercise of thought is, in the literal sense of that word, inference; by it one thing carries us over to the idea of, and belief in, another thing. It involves a jump, a leap, a going beyond what is surely known to something else accepted on its warrant.”

— John Dewey, How We Think (1910)

The physicality of this description is more than a metaphor. Movement and thinking are closely intertwined, interrelated and interactive, and not as separate from one another as we were trained to believe through our disconnected education system.

As animals we need to control our movements, so we can quickly get from one place to another, to safely move from the known into the unknown, and back again. Being able to jump and carry things increased our range of possible actions.

But as humans engaged in these complex, purposeful movements we are also at the same time continually talking to ourselves. This is why it is called internal dialogue. We are always having intercourse with our Selves.

As humans we need to control our thinking - our movements of thought - so we can quickly jump from one fact or idea to another; and to reason from the known (which is present) into the unknown (which is not yet present). We then use the products of thought to plan and guide our future actions, mentally simulating different scenarios before actually doing them, and therefore increasing our range of possible actions.

Some of the words we “say” are useful and focussed on the task at hand, but many, maybe even most, are either irrelevant or ineffective, or merely verbal labels attached to feelings and sensations. This inner speech, or self-talk, is what we most need to learn to control - it is what translates our thoughts into action, theory into practice.

Your inner speech is both a form of movement and a cause of movement. If you let it just happen by itself, then you also let your actions just happen by themselves.

Video:

On “Philosophy as a Way of Life” and “Spiritual Exercises”

This is part of a series by Dr Gregory Sadler on the excellent book Philosophy as a Way of Life by the French philosopher Pierre Hadot (highly recommended.)

The ancient philosophers had techniques and methods you were supposed to practice during your daily life order to enact their ideas and teachings. What most of these spiritual exercises have in common are “attempts at mastering inner dialogue.” (see 8:52)

This might surprise people but the key to having good POSTURE and COORDINATION for life is also…. mastering your inner dialogue.

Unorganised inner speech leads to unorganised movements and postures. You are giving yourself these verbal commands all the time, then carrying them out mechanically, whether you realise it or not. These are quite fuzzy, dominated by feeling rather than reasoning, and usually not well articulated: “My shoulders should be over here, my back should feel more like this, I like my feet better here, lean back like this, stand up straighter until feels better, stick my chest out until I feel tough etc etc.”

My lessons are based largely on the initial, earlier method of the young F. Matthias Alexander. His almost forgotten original technique is definitely in the tradition of these “spiritual exercises”, and a modern example of “philosophy as a way of life.”

To a certain point I am in sympathy with all workers in either "physical," "mental," or "spiritual" spheres, for I believe that "there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy," but it has always seemed to me that the first duty of man was and is to understand and develop those potentialities which are well within the sphere of his activities here on this earth.

— F. Matthias Alexander, Constructive Conscious Control of the Individual (1923/46)

His practical method is based on using verbal instructions, or “orders” or “messages” to plan and command your own movements in a new way - in accordance with what we would now call a mental model. Working on your posture is the perfect way to learn how to master your inner speech like this, because the results are visible and objective. You are closer to the model or you are not. You and your teacher can agree if you are making progress or not.

You can then apply this skill, or capacity, to other domains of life e.g. emotional regulation, memory, problem solving, writing, or anything else that requires control of movement and/or thinking (i.e. everything.) You learn to take control of your self-talk and so begin to align your thoughts, words and deeds. It is an art of living consciously. This bridges the gap between theory and practice.

In The Republic, Plato tells us we need to order the three parts of our soul and develop the four virtues. That’s great, but HOW exactly?! If the Greeks had a formal technique or practice that would be our culture’s historical equivalent to Zen, Yoga, and Tai Chi etc, then it has been lost to us. But based on certain sculptures, pottery art and written clues, I’m certain they did, and it is in part reconstructible (see future newsletters!)

Alexander’s earlier technique is amazingly similar in structure to The Republic Book 4, almost as if it was the “how to” guide to accompany the dialogue. So my approach is:

Plato tells me WHAT to do; Alexander tells me HOW.

(If you like the sound of this, take a 1-to-1 lesson with me.)

Myth:

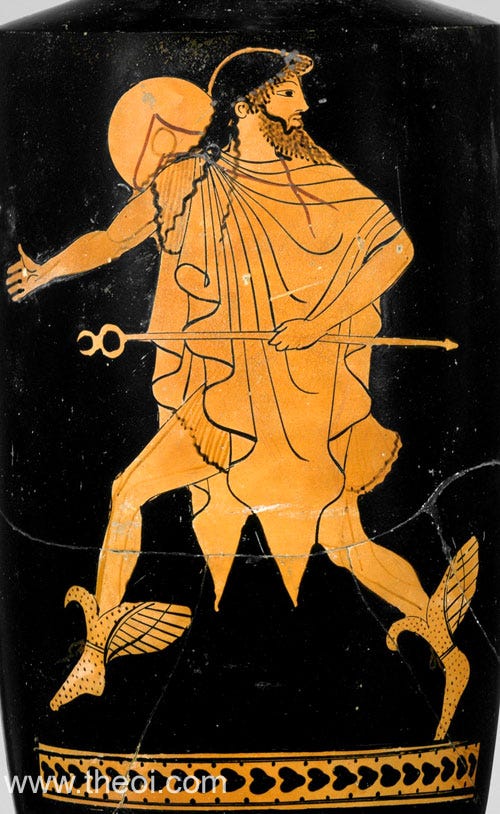

Hermes, Athenian red-figure lekythos C5th B.C

Hermes was the Greek god of heralds and diplomacy, language and writing, athletic contests and gymnasiums, among other things. This might at first look like an eclectic mix of attributes but if you squint at it PsychoPhysically then it makes more sense.

He is usually shown running with his winged feet/sandals carrying out his role as messenger of the gods. What are messages? Messages here are verbal commands (spoken or written) sent from one person and place to another. The end goal is usually to cause a specific action somewhere else, or prevent a specific action somewhere else.

Let’s say you want to master you inner dialogue, in order to correct your posture.

You can imagine your Conscious Will as Zeus, and the self-speech you use to implement your Will as Hermes. You can learn to send coordinated messages to the different parts of your body with the purpose of (1) causing definite actions e.g. new movements of specific body parts and (2) preventing definite actions e.g. incorrect movements you normally do on autopilot.

The myth of Hermes shows that, for the Greeks, to move quickly and to think quickly were the same skill or capacity: the ability to think on your feet.

If you want Winged Feet, speak Winged Words.

Quotes:

“Looking from under the eyebrows Achilles swift of foot spoke to him…”

“[Achilles] spoke to Her with Winged-Words saying…”

— The Iliad by Homer (book 1, translated by Juan Balboa)

Experiment:

“Think but don’t touch…”

The purpose of this simple experiment is to learn to see the interaction between your inner speech, outer speech, and movements.

Record yourself sitting face on to the camera, visible from the waist up.

Think of - but don’t touch yet! - the very top of your sternum bone (the bone just below your throat at the top of your chest) Locate it in your mind only - did you just move or twitch a little bit, did you feel that impulse?! a-u-t-o-p-i-l-o-t

Now with the tip of your left index finger touch the top of the sternum. Put your hand back down. How accurate was your aim? Did you find it first time?

Next, touch the sternum again, but this time: count out loud “1, 2, 3” as you do it. Start the movement on 1, and end the movement on 3. How accurate was your aim this time?

Finally, watch the video. (a) What do you see that you never felt at the time, were your opinions accurate? (b) Was there more fidgeting on the first attempt or the second attempt? (c) Which movement was smoother, more graceful? (d) What was the impact of counting out loud on your inner dialogue? (e) How did having the start & end times affect your movements?

Have fun talking to yourself,

Thanks for reading,

Kevin

P.S. If you want to turn words into actions, book a 1-to-1 lesson with me.

I will teach you psychophysical techniques and “spiritual exercises” designed to improve your posture and movements by mastering your inner speech.

For more info (1) reply to this email, or (2) message me on Twitter.

Fascinating as always, and I love the classical leaning to it all as this is one of those things that a pleb like me knows is important but has never quite gotten around to studying properly. Maybe I’ll try and get the group/cult to read some Greek and Roman classics in the coming months...

Cheers,

Tom.